'Voting while black': How activists are racing to create a midterm 'black wave'

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 10/30/2018, 8:20 a.m.

By Fredreka Schouten

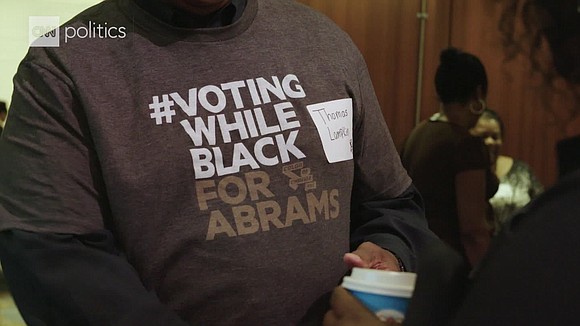

(CNN) -- On a drizzly Saturday morning, nearly 200 people gathered in a downtown conference center here for what was billed as a "black joy" brunch -- complete with mimosas, glasses of sweet tea and plates of fried chicken and waffles.

But the gathering wasn't merely social.

As a DJ blared Beyoncé's "Crazy in Love" over the sound system, the crowd of mostly African-American women pulled out their cell phones, logged into an online voter-outreach tool called Relay and began a texting marathon. In a little more than two hours, they had reached 65,000 infrequent African-American voters in a swath of rural Georgia, known as the Black Belt.

Their messages warned of purges of African-American residents from the voting rolls and urged support for Stacey Abrams, the Georgia Democrat who's vying to make history as the nation's first black female governor.

This brunch and a crop of other quasi-social events organized around the country by the two-year-old Color of Change PAC seek to drive black turnout in key states. That includes Georgia, where African-Americans make up nearly 31% of the population but, like many voters, sit out off-year elections in droves.

The event also illustrates how a little-known but growing network of African-American political groups is laboring behind the scenes to reshape who will vote in the midterms and engineer what Color of Change's executive director, Arisha Hatch, hopes will become a "black wave" that sweeps Abrams and other Democrats into power.

Their ultimate goal: build lasting political clout for African Americans, especially in the South, where more than half of the nation's black residents live. To do so, they will have to defy history and permanently change decades of voting behavior.

Faced with a "bigoted and destructive agenda" in Washington, "black voters are seeing this as a transformative moment for the country," said Adrianne Shropshire, who runs BlackPAC, a two-year-old political action committee.

"They are using their votes as their resistance," she said.

BlackPAC, which helped boost turnout for winning Democrats last year in Virginia and Alabama, is now spending $8 million in the final sprint to Election Day to target African-American voters with radio ads and mailers in Georgia and nine other states.

Other groups working to change the complexion of the midterm electorate include PowerPAC Georgia, a group affiliated with San Francisco lawyer and veteran Democratic strategist Steve Phillips, which is plowing in $5 million to help turn out 100,000 infrequent African-American voters who live outside the metro Atlanta area. Collective PAC, which bills itself as the EMILY's List for black candidates, is launching a national text-messaging program to reach about 2 million African-American voters in at least five states, including Florida and Mississippi.

The Black Economic Alliance, a group started in this election cycle by African-American executives, is spending $2.6 million in a last-minute voter-mobilization push in 15 federal and state races. Color of Change PAC, whose financial backers include labor unions and Democratic billionaire Tom Steyer, plans to spend about $5 million to reach 1 million black voters.

And a coalition of African-American groups, led by the Black Women's Roundtable is trying to mobilize at least 150,000 black women to vote in Georgia.

Several of these groups, including BlackPAC and Collective PAC, came to life in 2016, as African-American political operatives prepared for the end of Barack Obama's presidency and a new era in American politics.

Quentin James -- who co-founded Collective PAC with his wife, former Obama campaign aide Stefanie Brown-James -- said he also wanted to help turn the energy feeding Black Lives Matter protests into something more durable: greater political representation.

"People are saying, 'I don't just want to protest. I want to run. I want a seat at the table to make the change,' " he said.

"Hidden" figures

Black turnout helped swing two high-profile contests -- the battles for a US Senate seat in Alabama and Virginia governor -- to Democrats last year.

Exit polls in Alabama's special election for the Senate found that 98% of black women who voted in that election backed Democrat Doug Jones, helping him beat Republican Roy Moore to become Alabama's first Democratic US senator in a quarter-century.

Those voters and the black female activists who got them to the polls sparked comparisons from political commentators and late-night comedians alike to the little-known black female number-crunchers at NASA whose work, chronicled in the book and 2016 movie "Hidden Figures," helped the space agency achieve some of its biggest early accomplishments.

Now some of these strategists believe they could use the Alabama template to achieve something even bigger next month, when Abrams and two other African-Americans, Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum in Florida and former NAACP chief Ben Jealous in Maryland, compete in governors' races.

Like Georgia, the contest in Florida is highly competitive.

A recent CNN poll found Gillum 12 points ahead of his Republican rival, former US Rep. Ron DeSantis.

Meanwhile, in the Republican stronghold of Mississippi, another African-American candidate, former congressman and US Agriculture Secretary Mike Espy, is on the Nov. 6 ballot in a three-way US Senate race. Strategists in both parties say the contest, in a state with the highest percentage of black residents in the country, could end in a late-November runoff.

"We are in a special moment," said LaTosha Brown, the co-founder of Black Voters Matter, who worked on the Alabama race and now is leading a bus tour, dubbed "The South is Rising," to mobilize African-American voters in Georgia and other states.

"I see black excellence when I see a Stacey Abrams, a Mike Espy, an Andrew Gillum," she said in a telephone interview. "These are the candidates I have been praying for."

Republicans say it's unlikely these organizations can replicate the special election in Alabama, where Jones' rival, Roy Moore, faced accusations of sexual abuse. "All the controversy surrounding Judge Moore is what won that election," said Jason Thompson, a GOP national committeeman from Georgia.

"It's not organic," he said of the activity by groups flooding his state on Abrams' behalf. "I don't think it's going to have an effect on people."

The new African-American organizations say they expect to make gains with activism that extend far beyond the marquee races of the midterms.

Brown, for instance, is advocating for a referendum on the Nov. 6 ballot in Nashville that would create a civilian-led board to review police actions.

The Color of Change PAC is mobilizing voters to influence local prosecutor races around the country amid concerns about excessive police force. Wesley Bell, a Ferguson, Missouri, city council member who received support from Color of Change and the Collective PAC, in August toppled longtime St. Louis County prosecutor Robert McCulloch in the Democratic primary.

McCulloch had faced intense scrutiny over his handling of the investigation into the 2014 fatal shooting by a white officer of a black teenager named Michael Brown in Ferguson.

Georgia as ground zero

But for many of the activists, Georgia is ground zero in the battle to expand the midterm electorate.

They face rough terrain.

Georgia hasn't elected a Democratic governor in two decades. President Donald Trump won the state in 2016 by 5 percentage points.

Abrams' supporters hope the state's growing racial and ethnic diversity and substantial investments by voter-outreach groups, including the New Georgia Project founded by Abrams in 2013, will pay off next month -- and translate into electoral competitiveness in the 2020 White House battle.

"If Abrams wins or even comes close, I think it confirms the view that some of us have held for a while: that Georgia is becoming a swing state and that in the not-distant future ... could be up for grabs in the presidential election," said Alan Abramowitz, an Emory University political scientist.

But Chip Lake, a veteran Republican strategist in Georgia, said Abrams and her allies face stiff headwinds, in part because she's vying to succeed a popular figure in Georgia, two-term Republican Gov. Nathan Deal.

"Voters are really happy with the direction of state government," he said. "All things being equal, this is still a red state right now."

Less than two weeks before Election Day, the campaign between Abrams, a former Democratic leader of the George House, and her Republican rival, Secretary of State Brian Kemp, is neck-and-neck, raising the possibility that the race won't be decided next month.

A third candidate, Libertarian Ted Metz, trails far behind but could have a big impact on the outcome. If no candidate wins a majority on Nov. 6, the contest goes to a Dec. 4 runoff between the top two finishers.

The race has been rocked repeatedly by allegations of voter suppression, and those battles spilled into the candidates' first televised debate. Abrams argued that Kemp had "suppressed" voting and "scared" Georgians from the polls during his tenure as the state's election chief.

Kemp said he actually had lowered barriers. "We have a million more people on our voters' rolls today than we had when I took office," he said during Tuesday's faceoff.

Voting access remained a flashpoint for the groups trying to drive African-American turnout.

In an incident that quickly went viral, Brown's Black Voters Matter bus was stopped on the first day of in-person early voting from taking a group of African-American seniors to vote in Jefferson County, Georgia. A county administrator told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution he felt uncomfortable letting patrons of the county-run senior center leave with an "unknown third party."

Brown said the episode seemed to make the seniors, and other African-American voters who heard about it, only more determined to cast their ballots.

Brown said one of the older women forced off the bus that day later told her: " 'Baby, I got off that bus and went and got in my car and picked up my friend and both of us went and voted.' "

"So that one vote turned into two votes," Brown said. "We transformed what would have been a very devastating moment into a moment of empowerment."

So far, early voting is skyrocketing in Georgia.

Nearly three times as many people had cast ballots as of Friday afternoon as had during the same period in the 2014 midterm elections, according to statistics compiled by Georgia Votes, a privately run website tracking voting data. African-American voters accounted for 29.3% of the total.

Texting while dancing

Patricia Benjamin-Young, 51, said she had cast her ballot on the very first day of in-person early voting to ensure nothing got in the way of her support for Abrams.

Nearly a week later, encouraged by members of her church, the corporate auditor joined Color of Change's brunch and sent her very first peer-to-peer political texts.

In all, she communicated with about 30 people. Only one texted back "STOP," she said. One had voted already, and several others said they wanted to cast their ballots on Election Day.

"I felt good about knowing that people are getting out and are registered to vote," she said.

Benjamin-Young also had a little fun, joining dozens of other participants who clutched their phones and continued texting while dancing the electric slide. Other attendees posed for photos against a wall adorned with pink paper flowers.

Organizers encouraged the party atmosphere.

"Voter engagement in many states has become incredibly transactional," said Hatch of the Color of Change PAC. "Lots of folks hear from the candidates or hear from the party a week before the election, two weeks before the election, and they never hear from them again."

Hatch said her group instead wants to build a community of activists who will stay engaged after Nov. 6 in places like Georgia. "We are trying to make volunteering fun and build that muscle within families."

Erica Waverly, a 38-year-old union organizer, said politics runs in her blood. At age 3, she had already joined her father and five siblings on the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, to distribute sample ballots.

Now living outside Atlanta, Waverly brought her young daughters, Esa and Eri, to the text-a-thon "as a way of continuing the tradition," she said.

She expressed little doubt that Abrams would prevail, despite the ongoing battles over voting access.

"They'll be able to see the first black president in their lifetimes and the first black woman governor of Georgia and the country," she said as her girls ran around the conference center lobby, clanging a plastic toy cowbell. "It's a pretty awesome time to be alive right now."