Could Congress Stop Trump From Bombing North Korea?

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 8/21/2017, 8:36 a.m.

By Jeremy Herb, CNN

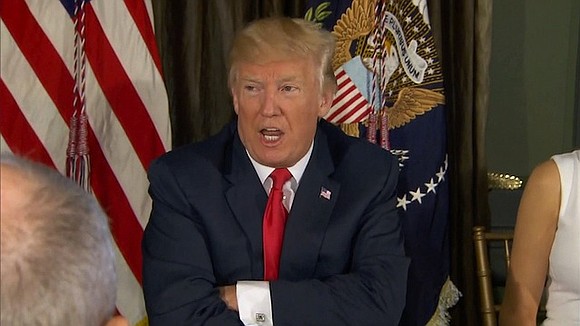

(CNN) -- President Donald Trump threatened North Korea with "fire and fury" Tuesday if Pyongyang doesn't stop threatening the United States. But can the President launch a military strike on his own?

The Constitution may give Congress the ability to declare war, but in reality it has little ability to stop the President if he's determined to strike North Korea.

That's because the President has his own authority as commander in chief to defend the country from threats, and in practice the Executive Branch has used that authority for a range of military actions.

Congress could pass a law prohibiting the use of force or blocking funding for military action in North Korea. But short of an outright ban, the Trump administration would have authority to act for at least 60 days as it if determines the US is under threat, according to national security and legal analysts.

"The Constitution gives tremendous authority for the president of United States to act on his own," said Roger Zakheim, a former House Armed Services Committee aide.

"Both in terms of constitutional law and in practice, for the President to take military action there's a lot of precedent if the perceived act of belligerence puts the national security of the United States at risk," added Zakheim, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and lawyer at Covington and Burling.

In the wake of Trump's "fire and fury" comment on Tuesday, lawmakers began calling for Congress to authorize any preemptive military action against Pyongyang.

Sen. Dan Sullivan, an Alaska Republican, told CNN's Erin Burnett a preemptive strike would require congressional approval.

"The administration has done a good job up until now working closely with the Congress on their broader strategy. But we're going to play an important role here," Sullivan said Tuesday night.

Michigan Democratic Rep. Dan Kildee told CNN's Poppy Harlow on Wednesday Congress should weigh in, especially with Trump in the Oval Office.

"This is a conversation that needs to take place. The authority of congress should be asserted, particularly in the case of this president where he seems to be somewhat erratic when it comes to what he suggests is American foreign policy," Kildee said.

But the White House takes a different view about the role of Congress and the Trump administration did not go to Capitol Hill for approval of its military strikes against the Syrian regime.

In April, then-press secretary Sean Spicer was asked if the President was prepared to act alone on North Korea or if Congress should be involved.

Spicer responded Congress would be notified, but said the President would "utilize the powers under Article II of the Constitution," which covers the Executive Branch.

"I think what you saw with respect to the action that he had with Syria, he made sure that members of Congress were notified of his action in a very, very short amount of time," Spicer said. "We're going to continue to seek their input on the policy overall and then make sure that they're notified."

The disconnect between Capitol Hill and the White House lies in the disagreement over what constitutes a threat to US national security, a question that comes with lots of legal ambiguity that gives the Executive Branch wide latitude.

Steve Vladeck, a CNN legal analyst and professor at the University of Texas School of Law, said the Constitution effectively distinguishes between offensive military action, which requires congressional approval, and defensive military action, which does not. But in practice, it comes down to more of a political question than a legal one.

"It's probably the case that Congress could not stop the President from defending the United States from an imminent attack. It probably is the case that Congress could prevent the President from launching offensive military operations without provocation. And all of the fight is over the gray area in between those two points," Vladeck said. "Where the line is between defense and offense?"

The administration viewpoint has varied from administration to administration. Under President Barack Obama, many lawmakers argued he should not have taken military action in Libya without coming to Congress first, but Obama did seek congressional approval to strike Syria — a process that ultimately led to the Obama administration not taking military action.

"On the practical level, the most effective power of Congress is their public role," said Katherine Blakeley, a defense analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. "That was in large part what scuttled Obama's ambitions to have Congress authorize use of force for Syria in 2013."

Congress has passed some constraints on the President's military power. The 1973 War Powers Act -- passed over the veto of President Richard Nixon -- requires the President receive congressional approval for any hostilities lasting longer than 60 days.

Every administration since, however, has argued that portions of the law are unconstitutional -- and in this case, 60 days could be an eternity in a conflict with North Korea.

"In this situation, the President's powers are at its zenith, and even though the Constitution says it's Congress' responsibility to declare war, the President with speed of conflict can change facts on the ground before Congress can even call a quorum," said Mieke Eoyang, a national security analyst at Third Way and former congressional aide.

Marty Lederman, a professor at Georgetown Law School, argued the President does need to go to Congress before striking North Korea — unless there's a truly imminent threat — because US military action could spark a major conflict.

"This would be as consequential and as risky a military action as any that's been contemplated in the last half century," said Lederman, a former official in the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel.

There are some steps that Congress could take ahead of military action. Congress could try to block it by prohibiting funding for offensive strikes against the North Korean regime. The idea of using appropriations to curtail military action was debated during the Iraq War when Democrats took control of Congress in 2007.

Two Democrats, California Rep. Ted Lieu Massachusetts and Sen. Ed Markey, aimed to curtail Trump's ability use nuclear weapons, introducing legislation in January that would prohibit a first-strike nuclear launch without Congress first declaring war.

Congress could also pass an outright prohibition, but it would surely be vetoed by the President -- and there's nowhere near a veto-proof majority currently to make such a provocative move legislatively.

"I can't think of any time in history where Congress has preemptively taken action to preclude the president from taking some sort of military action," said Jennifer Daskal, a former Justice Department official and professor at the American University Washington College of Law. "It would be pretty unprecedented."