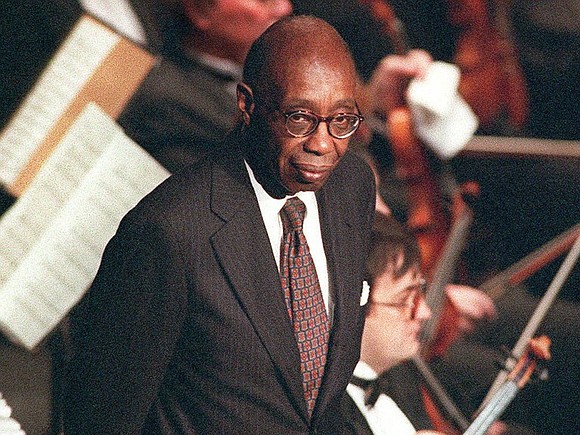

R.I.P. George Walker, 96, Trailblazing American Composer and Pulitzer Prize Winner

Style Magazine Newswire | 8/28/2018, 4:22 p.m.

by Tom Huizenga via npr.com

Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, pianist and educator George Walker has died at the age of 96. Walker’s death was announced to NPR by one of his family members, Karen Schaefer, who said he died Thursday at Mountainside Hospital in Montclair, N.J. after a fall.

Walker’s music was firmly rooted in the modern classical tradition, but also drew from African-American spirituals and jazz. His nearly 100 compositions range broadly, from intricately orchestrated symphonic works and concertos to intimate songs and solo piano pieces.

“His music is always characterized by a great sense of dignity, which is how he always comported himself,” says composer Jeffrey Mumford, who, as a music professor at Lorain County Community College in Ohio, uses examples of Walker’s music in his classes. “His style evolved over the years; his earlier works, some written while still a student, embodied an impressive clarity and elegance.”

Walker was a trailblazing man of “firsts,” and not just because of the Pulitzer. In the year 1945 alone, he was the first African-American pianist to play a recital at New York’s Town Hall, the first black instrumentalist to play solo with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the first black graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

The following year, Walker wrote his first string quartet. In 1990, he revised the second movement into a new piece, Lyric for Strings, which has become his most often-performed work.

In 1996, Walker broke new ground again when he became the first African-American composer to win a Pulitzer Prize for music. Lilacs for voice and orchestra, set to a text by Walt Whitman, is a moving meditation on the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

George Theophilus Walker was born June 27, 1922 in Washington, D.C. to a father from the West Indies and a mother who started him off with piano lessons at age five. At 14, Walker gave his first public recital at Washington’s Howard University. In 1937, he entered Oberlin College in Ohio on a scholarship and graduated at age 18. He then enrolled at the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he studied piano with Rudolf Serkin and composition with Samuel Barber, graduating in 1945. In the late 1950s, he traveled to Paris to study for two years with the famous pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. (Her other students ranged from Aaron Copland to Quincy Jones.)

Mumford likes to recall a story about Walker’s Paris years with Boulanger. “She was so impressed with his musicianship that she waived the regular requirements she made of students,” Mumford says. “He could bring anything he wanted to show her at lessons.”

Walker’s reputation as a composer of works for orchestras like the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra and the Boston Symphony slowly grew, but Mumford says Walker’s fame was hard-won.

“We have a great deal of work to do regarding orchestra programming of composers of color,” Mumford says. “Walker deserved many more performances than he has received thus far. Sad to say that even the work that earned him the Pulitzer has not graced the concert hall nearly enough.”

Walker is often identified as an “African-American” composer instead of simply an American composer. In a 1987 interview with broadcaster Bruce Duffie, Walker said there are two sides to that label.

“I’ve benefited from being a black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by black composers, I would get performances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works,” Walker said. “The other aspect, of course, is that if I were not black, I would have had a far wider dispersion of my music and more performances.”

Mark Clague, who wrote the entry on George Walker for the International Dictionary of Black Composers, points to elements of race and politics in Walker’s compositions.

“He constructs his music so that the unknowing listener should not be able to distinguish it from that of his ‘canonized’ white contemporaries,” Clague writes, citing influences from Stravinsky, Debussy and the serialist school of composers. “He frequently draws on black musical idioms, such as spirituals, blues patterns and jazz tropes. Walker’s music, however, is not a collage of modern styles, or a pastiche, but has its own distinct voice.”

In 2009, Walker told NPR’s All Things Considered that as a composer, right from the start, he knew he had to become an individual. “I had to find my own way,” he said. “A way of doing something that was different, something that I would be satisfied with.”

Walker is survived by two sons: Ian Walker, a playwright, and Gregory T.S. Walker, a violinist and former concertmaster of the Boulder Philharmonic Orchestra in Colorado, who said that his father was still active, working on commissions at the time of his death.