Libraries oppose censorship. So they're getting creative when it comes to offensive kids' books

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 3/4/2021, 11:43 a.m.

By Scottie Andrew, CNN

(CNN) -- It's a wondrous thing to introduce a child to a beloved book, to read with them as they enter a literary world generations before them have enjoyed.

But the nostalgia and thrill of bonding over a book makes it all the more crushing when an offensive paragraph stops the young reader in their tracks.

It's an ugly surprise present in classics like "Little House on the Prairie," "Peter Pan" and several Dr. Seuss picture books -- racist depictions of indigenous, Black and Asian characters that mar some of the best-loved works in children's literature.

It's hard to imagine a children's library collection without those titles. It's up to librarians, then, to determine whether those books and others with racist content still deserve a spot on their shelves, said Deborah Caldwell Stone, director of the American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom.

"We may make a reevaluation of those books and their place in the canon," she told CNN. "It doesn't mean that people should stop reading the books or not have them in their collection, but they should be thinking critically about the books and how they are shared with young people."

The American Library Association vehemently opposes literary censorship. Rather than remove the offending books from their collections, librarians have come up with creative solutions to educate young readers, so while they may still delve into Laura Ingalls Wilder's pioneer adventures or Seuss' zany world of anthropomorphic animals, they'll come away knowing what's wrong with those stories -- and which books get diverse stories right.

The books may still stay on shelves

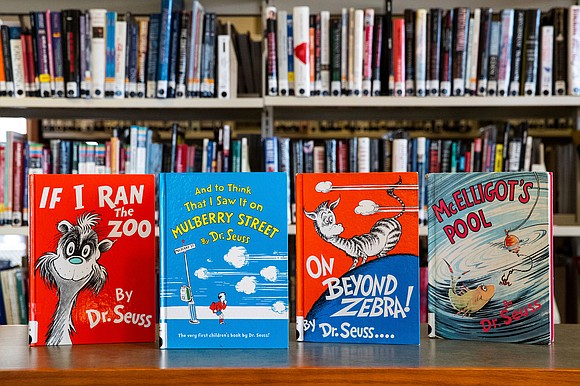

Parents, critics and readers of all ages reignited arguments over offensive children's books this week when Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced it would cease publication of six of the famed author and illustrator's books that contain harmful portrayals of minority groups.

Librarians have been paying close attention to the debate for years. Staff members who lead story times or curate displays are more likely now to select more inclusive titles than stalwarts like Seuss and Ingalls Wilder, Caldwell Stone said.

"The fact is that library collections are dynamic," she said. "There's only so much shelf space, and over time collections will shift."

Some libraries may move an offending book to the adult collection or historical archives, where it can live as a "historical artifact" that reflects the dominant attitudes of the time it was published.

But perhaps the most important consideration a librarian has is the wants and needs of their readers -- is a book reflective of the community the library serves? Is it still popular among readers? If a librarian decides a book is "no longer serving the needs of the community," it may be weeded out, Caldwell Stone said.

Offensive books can be conversation starters

"Little House's" stories of homesteading in the West and the Neverland adventures of a boy who flies but never ages are tales of daring, friendship and resolve. But both also contain racist depictions of Native Americans and fictional indigenous people, text that is often accompanied by offensive artwork in many editions.

And in Dr. Seuss' "If I Ran the Zoo," one of six books by the famed author that will no longer be published, characters intended to be of East Asian descent, with long wispy mustaches and closed eyes, carry a caged animal on their heads. It also features two people drawn as members of an unnamed African tribe with dark skin, large bellies and grass skirts.

The lens of nostalgia, coupled with the fact that most parents likely haven't revisited children's books since their own childhood, may've caused some adult readers to forget these offensive details. If parents do choose to introduce these books to their children, though, they can use the texts as launchpads for discussion of complicated topics like racism, Caldwell Stone said.

"The decision by Dr. Seuss Enterprises is a chance for adults to think critically about the books, decide whether or not to share them with the children in their lives and to engage in that conversation about race and racial prejudice," she said.

In 2019, staff at the Nashville Public Library started those conversations with their own children in a series called "Tackling Racism in Children's Books." Librarians read classics with their kids, stopped at offensive passages and asked them questions about what they thought about the text or image and why it was hurtful.

Librarian Lindsey Patrick read "Little House on the Prairie" with her young daughter and repeatedly probed her about why Ingalls Wilder's portrayal of Native Americans as cruel and unsophisticated was wrong. Some of the questions went over her daughter's head, Patrick wrote in a blog post for the library, but her daughter recognized that the "Indians" in the book were more offensive stereotypes than fully formed characters like Laura, Ma and Pa.

"Maybe my daughter didn't walk away with a full understanding of white privilege, but she can now better identify when someone is being 'snotty' to another person for racial or cultural differences," she wrote in 2019. "She also has a better understanding of our country's treatment of its native people."

It's a chance to add new books to the canon

The debate around Seuss and other popular classics is an opportunity for librarians to reevaluate the books that belong in canonical children's literature -- that is, books that are considered the best-loved and are frequently taught and read.

"I don't think that older books will be left behind -- I think that the canon will be expanded, and our understanding of what is important literature will be expanded" to include the experiences of Black Americans, people of color and other marginalized groups, Caldwell Stone said.

Librarians at the Brooklyn Public Library have for years left classics on the shelves and for story times select titles that celebrate "the diverse voices and experiences that help create the fabric of the Brooklyn community," said Amy Mikel, the Brooklyn Public Library's director of customer experience.

Online, the library curates lists for parents and young readers on specific topics, like books to read on Indigenous People's Day, such as "I Am Not a Number;" picture books with Black protagonists, like "Don't Touch My Hair" and alternatives to "Harry Potter" that feature LGBTQ-friendly magic schools, like "Not Your Sidekick."

Books with offensive content remain available to check out, she said, but they better serve readers as a "springboard for conversations and healing." The library's attention remains on widening its selections that center members of historically marginalized groups.

If a classic is still popular, librarian Kaitlin Frick wrote in a blog post for the Association for Library Service to Children, library staff should attach to it a guide for discussing racism for parents and young readers. She also suggests librarians encourage parents to check out anti-racist books or more inclusive titles along with a classic book.

Spotlighting books that feature diverse characters while sidelining, but still offering, books that reduce diverse characters to stereotypes is an option that sticks to librarians' anti-censorship stance and, hopefully, carves out a place for more books to join the wider canon of notable children's literature, Caldwell Stone said.

"It's always been the role of libraries to foster cultural understanding," she said. And with a larger emphasis on books that don't rely on stereotypes and prejudice to entertain, librarians hope, libraries can be havens for readers from all backgrounds.