Lovell's Food For Thought - Again I Ask The Question, Isn't It Time We Really Do Something To Do Something

Passed Time To Really Do Something

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 5/21/2022, 11:57 a.m. | Updated on 9/17/2022, 8 p.m.

In the 60 plus years I have been involved with equity issues, I have come to see very little true progress in significantly reducing health inequities. I have seen a significant increase in the number of seminars, workshops, programs, centers and/or institutes, but reductions in death disparities the answer is NO. The COVID-19 Pandemic has made this apparently clear, that what we are doing is not working. The question is what are we going to do about it other than hold more meetings and give speeches on how we increase our efforts to address this as a national priority?

I believe that most of our intentions are well meaning, but again COVID-19 truly begs this question, do we really want to solve this issue facing America or do we just want to play at it to make ourselves feel good while those who suffer disparities continue to die disproportionately ? I have come to see the health industry as just doing something for show and profit, winning awards, being named number one and so on. But what does it do for the communities of color when people are still disproportionately dying. I have written over 100 Op Ed pieces on this issue. But what I have found out is that most are just as good today as they were the day I wrote and published them. All I need to do is basically change the date and that is what I am doing with this one..

For instance, It was truly disappointing that NO ONE responded to the American Cancer Society's (ACS) Report earlier this year when it reported that cancer disparities were no different from when they started reporting. I saw nothing in the national media or even in the minority press saying enough is enough.

When I sent out two evergreen pieces recently, a Washington Lobbyist, who worked with me and the Intercultural Cancer Council (ICC), wrote this to me as I got some blow back accusing me again of being my negative self.

“ It is a very sad but a fascinating truth that in an attempt to control you, the powers to be at Anderson and elsewhere sent out conflicting messages about you - some revered and often reviled. The latter is mostly deceptively done. The powers to be purportedly agreed with the substance of your message but not your style of delivery. What crap. You were one of a very few true health equity and disparities warrior pioneers. Compared to the rhetoric today, your approach was quite statesman like. The folks who are leading today stand on your shoulders. No wonder why your spinal canal is narrowing and Marion demanded that you retire after suffering from years of stress!

So please take care of yourself, Lovell. You have many friends and colleagues who are praying for you and Marion. We know what you accomplished and the price you paid with humor and grace (most of the time). So long as those still out there challenging the system, the question you asked about how many Black women needed to die before something is really done will continue to be answered by the continuing excessive death.”

I asked about the kind of algorithms Facebook or LinkedIn uses, because it seemed as if to block certain posts I have been making about addressing health Inequities. One of my post asked again the question I originally asked at the Breast Cancer Integration Panel for the Department of Defense several decades ago - How many Black women needed to die of Breast Cancer before we really address the issues of health disparities , the backlash was swift. But over two decades later we have our answer, NOT ENOUGH!!! In 1998/1999, Frank Michel wrote two editorials, one entitled Racism can be cancer on the health system ,September 21, 1998. The second one came about because the first it too, generated a backlash of calls accusing him of not having a brain - No-brainer to broaden fight against cancer , February 1, 1999. Again, have we really made any progress since these editorials? Well the answer comes in the ACS report: “Alarming” health disparities in preventable cancers persist as overall cancer mortality continues to fall."

So, let me broaden my questions to how many people of color need to die before we really do something other than isolated attempts and the creation of positions or Taskforces or Centers. What I continue to say is we need to develop and implement a National Will. As Vince Lombardi once said “The difference between a successful person and others is not a lack of strength, not a lack of knowledge, but rather a lack of will.” I paraphrased it to say “The difference between successfully addressing health disparities is not a lack of emphasis, although more is needed, not a lack of knowledge, although more is needed, but rather a lack of will. There is evidently no truly National Will to solve problem. For Health Disparities has become an industry unto itself. Why, in my opinion, because we have yet to value human lives on an equal plane (http://stylemagazine.com/news/2015/oct/12/lovells-food-thought-silent-racism-value-human-lif/)), one of my evergreen editorials.

I recently said you don’t have to be racist to be racist; think about it. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/lovell-allan-jones-phd-6661037_health-inequity-activity-6906421930828668928-PqqG?utm_source=li

So you can judge for yourself, here is the first editorial written by Frank Michel in the Houston Chronicle. Please tell me what changed other than the names on the battlefield.

Racism can be cancer on the health system

CANCER. The "Big C." The warning signs can be oh-so-subtle. Or they can be boldly in-your-face alarming.

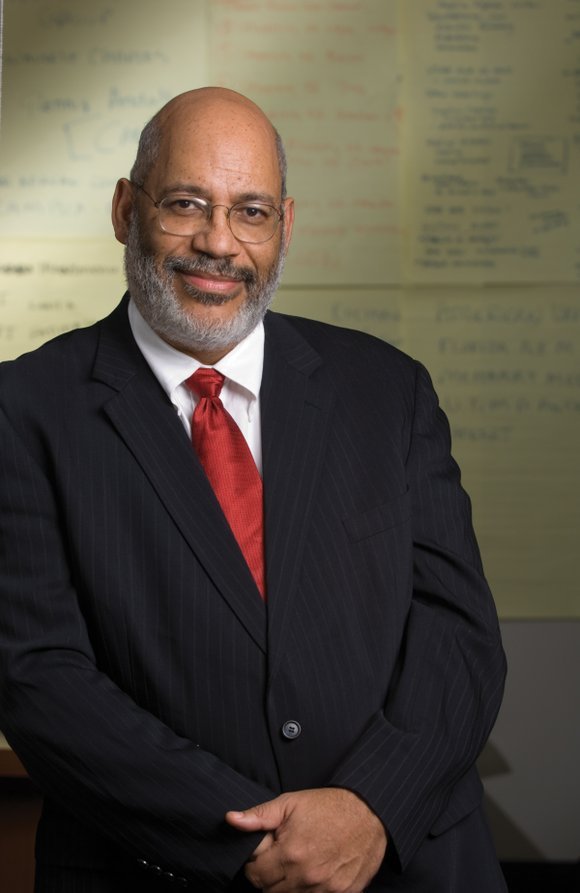

And in the wide, herculean effort to prevent and cure the many forms of the disease, Professor Lovell Jones is willing to play either of those roles, as needed. He's a one-man warning sign of what he sees as a cancer on the health-care system - racism.In any conversation with him, one is liable to get both of those approaches. It's because he is utterly committed to preventing both the cancer of the human body, and the cancer of the medical community's body politic.Jones, a native of Baton Rouge, is a professor and director of the Experimental Gynecology-Endocrinology Laboratory in the Department of Gynecological Oncology at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center here.Yes, it's a mouthful. But what Jones does and says and represents also speaks volumes.Some facts are clear. While cancer death rates are declining nationwide, according to the Intercultural Cancer Council in which Jones has been instrumental, racial and ethnic minorities are experiencing higher incidences and lower survival rates."Even minority members of the well-educated, well-insured middle class are likelier than their white counterparts" to have higher rates of certain cancers, Bridget Shulte of the Philadelphia Inquirer recently reported and documented in an excellent series of stories on such issues.Lack of space and my admitted lack of expertise compel me tell you simply that some cancers in some minority communities are epidemic. There is plenty of evidence of that. And it doesn't take much work to track down the documentation.What is not always so clear is to what degree racism plays a role in it. But the case is pretty compelling that racism is a factor somewhere along the line. And Jones minces no words in making that case.Benign neglect, institutional discrimination and internal politics, he will tell you, have left us with a system that has been unresponsive to both research and health-care needs."Few mainstream research institutions or government agencies have addressed minority health in a pro-active manner," he says. Most take a reactive approach when some legal or social pressure is applied.The problem begins with a lack of programs that mentor or steer minority students into the medical sciences, Jones says. It goes on to affect research agendas, research funding and national health policy issues which are often totally blind to minorities' needs and differences.Problems are ignored. Boat-rockers like Jones are ostracized or patronized or shunted off into corners by good-old-boy networks. Racial and ethnic biological factors are overlooked in research projects. Cultural differences are not factored into scientific data gathering. Minority doctors and researchers are paid less, promoted less, put down as trouble-makers or just tolerated. Like cancer itself, the disease can take many forms and many disguises that often make it hard to detect, hard to prove and very hard to eradicate.Curing, treating and prevention, after all, must begin with diagnosis and acknowledgment.You needn't agree with Jones. But I think it unwise, unhealthy and probably pretty costly - both in human and financial terms - to ignore him and others like him.At the very least, you have to admire a man who took on the role of activist against the advice of friends and colleagues who said it would jeopardize his career as a scientist. In the staid and sober world of medical science, it's a risk indeed.But, Jones' work in the laboratory and with the Intercultural Cancer Council and in other forums has to some large degree proven that one can do both good science and good, healthy activism successfully.Later this week, there will be events here and a march on Washington, D.C., that mark a national grass-roots effort entitled "Coming Together to Conquer Cancer." The ICC will be heavily involved in carrying the message of Jones and others that - for whatever reasons, which probably do include some racism - the needs of minorities cannot decently be overlooked in the fight against cancer.When he is vocal about these issues, Jones says, people too often "look at the messenger as opposed to the message."He is admirably dogged. "I refuse to be treated as a second-class citizen and I will scream and holler to cast light on the shadows."And his message may just catch the eye and the mind of someone who reads the column of a newspaper guy who thinks it is, at the very least, worth putting up to the rigors of scientific and social inquiry. We, together, need to prevent and cure cancer - cancer of all types.

Here is his follow up Op Ed after he was told he lacked a brain.

No-brainer to broaden fight against cancer This was written by Frank Michel nn February 1, 1999 in the Houston Chronicle.

IT was refreshing, being told by callers that I needed a brain transplant and that I should blow my liberal brains out. We in the newspaper opinion business usually get accused of having no brains at all.

I got those phone calls from angry readers several months ago when I used this space to, correctly, report how discrimination - deliberate and unintentional - within the nation's medical establishment - including in the Texas Medical Center - has led to a different, and sometimes deadly, double standard. In care, treatment and research efforts, differences among ethnic minorities have simply not been noted and treated with the same zeal as "mainstream" medicine and prevention. The same hasbeentrue with regard to gender, with women getting the short end of the proverbial stick until very recent times. And in the fight against cancer, the consequences have been particularly tragic.Those with hasty conclusions about my brain or my ideology can stop reading and start dialing here. Those with more open minds might want to read on and learn more.A congressional hearing was held last week to hear testimony about a brand new study by the Institute of Medicine, established in 1970 as part of the National Academy of Sciences and which advises the government on health issues.The study, requested by Congress in 1997 and entitled "The Unequal Burden of Cancer," arrived at several key findings:That the National Cancer Institute lacks the necessary database concerning the disproportionate cancer incidence, mortality and survival rates among ethnic minorities and the medically underserved to develop effective cancer control strategies for these populations.That "research so far has failed to take advantage of the diverse populations of the United States in understanding the causes of cancer and reducing mortality.That NCI actually spent only about 1 percent of its budget - about $24 million - on such research, while it claimed to have spent $124 million. (Even if its claims were correct, it would represent only 5 percent of its budget.)That the priority-setting process for research fails to serve the needs of minority and medically underserved groups.That there has been "inconsistent progress" in increasing the number of scientists from these groups and even determining whether training programs are producing the numbers of scientists and medical professionals from and representing these populations.The list goes on, but you get the picture. In other words, the problems, for whatever reason, are real, with real consequences."This study confirms what we've known all along," says Lovell Jones, a professor and director of experimental gynecology and endocrinology at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. "That all ethnic minorities and the medically underserved have not shared equally in the nation's progress against cancer."The outspoken Jones is also co-chairman of the Intercultural Cancer Council which is urging the NCI to take the report's findings into account.African-American men are 15 percent more likely to develop cancer than white males. Liver cancer rates among Asian-Americans are several times those of whites. Native Americans have the poorest cancer survival rate of any group.None of that's ideology. That's statistical and scientific fact that deserves a fair hearing.And the ultimate point of fairness is clear. It's a no-brainer that the fight against cancer should be broadened. Studying cancer rates among smaller groups of "special populations" will allow researchers to more accurately measure the impact of such things as "cultural and behavioral factors, beliefs, lifestyle patterns, diet, environmental living conditions and other factors," says the new IOM study.Only recently have we as a nation awakened to similar problems with regard to gender. A report in the latest volume of The Journal of Gender-Specific Medicine cites some gains made in recent years since women's health became more of an issue. These include Congress' reauthorization of the Mammography Quality Standards Act, which aims at ensuring women receive accurate mammogram results. A provision was even added requiring that patients have direct and timely access to mammography results.These are the kinds of considerations that the IOM study was intended to foster. What, I ask, is wrong with that?As for ideology, brain tumors don't distinguish between liberal and conservative brains and neither should our consideration and debate of these issues. Those who want to dismiss these concerns as brainlessness are, of course, free to do so. They, I suggest, may need to see somebody about their heartlessness.

The sad part is that although the Houston Chronicle pieces were written in 1998/1999, over two decades ago. They still rings true today. Even sadder is the fact that there is still no response to the lack of improvement from our leaders, no plan of action with clear guideline and measurable to document that we are making progress. just Presidential statement about doing this togehter. How many times have i heard this on some form?