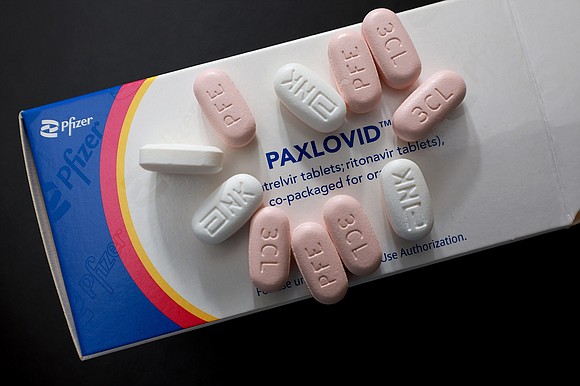

Covid-19 rebound may be more common in people who take Paxlovid, early study suggests

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 11/18/2022, 12:21 p.m.

Originally Published: 16 NOV 22 15:03 ET

By Brenda Goodman, CNN

(CNN) -- Cases of Covid-19 rebound following treatment with the antiviral medication Paxlovid -- where infections rev back up again after people complete their five-day course of the medication -- appear to be at least twice as common as doctors previously knew, a new study suggests. Covid-19 rebound also seems to be more common in people who take Paxlovid compared with those who don't take the antiviral, although it can happen in either circumstance.

In the past few months, instances of Covid-19 rebound have peppered headlines. President Joe Biden, first lady Jill Biden, as well as Dr. Anthony Fauci, who advises the president on pandemic strategy and Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have all revealed that their Covid-19 infections returned after they finished taking Paxlovid.

"Worst. Sequel. Ever," quipped comedian Stephen Colbert on Twitter after his rebound case in May.

These high-profile cases have led to social media speculation that the rebound might not be as infrequent as some studies have concluded. So far, studies have suggested that around 5% of people who take Paxlovid will experience a rebound.

Understanding rebound

In June, Pfizer, the company that manufactures Paxlovid, published an analysis of data from the drug's clinical trials showing that Covid-19 infections came back both in the group that got placebo pills and those who took Paxlovid, somewhere between 2% and 7% of the time. That study found rebound happened about twice as frequently in people taking Paxlovid as in those who took the placebo.

Another study in June, led by researchers at the Mayo Clinic, reported that only four patients out of 483 -- less than 1% -- who took Paxlovid experienced a return of their Covid-19 symptoms after treatment.

Most studies of rebound have had a significant weakness, however: They reviewed patient records, looking back in time, to count cases that recur.

That approach likely undercounts the true number who experience this phenomenon because it misses people who rebound at home, and either don't have any symptoms with their rebound -- they just test positive again on a rapid test -- or have symptoms so mild they don't feel the need to go back to a doctor.

The new study, led by researchers at Scripps Research Translational Institute and the telehealth company eMed, has an important advantage in this regard. It is one of the first to follow Covid-19 patients forward in time to measure cases that come back.

The study included 170 patients who came to eMed for testing and who were deemed by their doctors to be eligible to take Paxlovid because they were at high risk for developing severe symptoms from Covid-19.

They were invited to join the study only after they decided whether they wanted to take Paxlovid, said lead study author Dr. Jay Pandit, who is director of digital medicine at Scripps, in an interview with CNN.

"We didn't want to bias or influence their decision to take Paxlovid or not," Pandit said.

Early results suggest rebound may not be rare

The study also has some important limitations that make its conclusions imprecise. It is just getting started, so these first results come from a relatively small group of the first patients enrolled -- 127 who took the drug Paxlovid and 43 people who were eligible to take it but declined. Those 43 people served as a comparison group.

The study doesn't have enough statistical power to tell whether the differences observed between the two groups were due to chance or the treatment. Researchers say they eventually hope to enroll a total of 800 people, a study size that should yield clearer answers.

After people agreed to participate in the study, they were shipped a kit with 12 rapid home tests. They were advised to test every other day. They were also asked to answer questions about their symptoms.

Among the 127 who took Paxlovid, about 14% saw their viral loads climb again after treatment. This group tested positive for Covid-19, tested negative after completing their 5-day course of Paxlovid, and then tested positive again a few days later. About 19% saw their symptoms return after they completed their Paxlovid treatment although they may not have tested positive again.

Some of the people in the comparison group also experienced rebound -- though it appeared to be less common for these patients compared to the group that took Paxlovid. About 9% of the 43 people in this group tested positive again after initially clearing the infection and about 7% of the reported that their symptoms returned.

So far, Pandit said, the study is showing two main things: As many have suspected, Covid-19 rebound appears to be more common than previous research has suggested; rebound can also happen whether or not you take Paxlovid.

"The incidence rates [reported by previous studies] have had huge varying numbers, and most of them tend to be in the single digits," Pandit said. "The message really is we're seeing higher numbers of incidents," he said.

The study was published as a preprint, ahead of peer review.

Researchers who were not involved in the study agreed that it was on the right track and said the numbers it is gathering would firm up over time. It should also help answer the question of whether rebound is really more common after people take Paxlovid.

"There is an indication that symptomatic rebound is more frequent in Paxlovid-treated participants than in untreated controls, but larger numbers are needed to draw confident conclusions," said Dr. Michael Charness, chief of staff for the VA Boston Healthcare System. Charness has been documenting cases of Paxlovid rebound, including his own.

More testing planned

Pandit says they will continue to follow study participants and plan additional rounds of tests to try to answer other lingering questions like " 'why does rebound happen in the first place? And is it possible to avoid rebound by adjusting the dosage or duration of treatment? Does rebound have anything to do with long Covid?' "

Right now, there's no consensus about what should be done in cases of rebound.

At least one study has documented a case of a person with rebound Covid-19 who took Paxlovid and passed the infection to an infant.

Typically, rebound cases are mild and resolve within a few days. Fear of a rebound shouldn't keep anyone from taking the medication in the first place, Pandit says.

"There is a lot of underprescription of Paxlovid. We know it reduces hospitalization rates, reduces progression of symptoms, we know that, and we don't want to fuel the fire of underprescription," Pandit says.

In clinical trials, Paxlovid was nearly 90% effective at preventing hospitalizations and deaths in high-risk patients. As the virus evolves to beat other types of treatments, Paxlovid has continued to work.

By the same token, Pandit says, the uncertainty about rebound is almost certainly making people hesitant to use the drug. Studying rebound, he says, should shed important light on the problem and help to arm people with knowledge.

"We need to understand that one of the causes for underprescription is this misunderstanding of what the incidence rates really are," he said. "It's something we need to look at, so that we can counter it."