Addressing Race in the Classroom: PVAMU faculty, staff lead new book project to help foster safe academic environment

By Whitney Stovall | 5/1/2023, 4:35 p.m.

School districts and higher education institutions around the country are reexamining the place of race in the classroom due to state Republican influence. Much of the controversy surrounds the inclusion of Critical Race Theory, which makes white Americans face this country’s racist traditions.

The Crucial Conversation Hoston Foster And CambriceCRT is a lens to analyze historical policies and laws at a high level to understand how racism impacts all aspects of society, including housing, education and economic development, examining ‘separate but equal’ policies and institutional segregation.

Twenty-five states have proposed legislation prohibiting CRT instruction and related topics in schools, and eight have successfully banned discussion. The bills potentially limit what’s taught to students, professional development, resources and other activities that deter bias and promote equity in schools and communities.

However, banning race discussions in schools creates a division between the majority and Black and Brown students, who are left feeling undervalued and disconnected from the content.

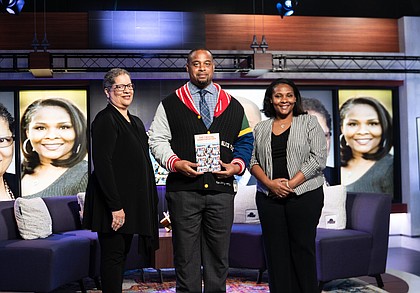

Instead of being discouraged by the political and social opposition to the discussion of race-related instruction, nine Prairie View A&M University faculty and staff members were motivated to provide teachers with a tool to help navigate conversations. Their newly released book, “The Crucial Conversation: Educating through an Anti-Racist Lens,” equips educators with the best practices for teaching and learning about race and racism in a post-George Floyd America.

“Even though this book talks about race and racism, it’s much more than a conversation about color. That’s just one piece of it. Addressing these concepts with our faculty helps to move them into the next generation. Maybe it can improve conversations at home; it certainly will help enhance conversations in the classroom,” said co-editor Laurette Foster.

Preparing educators to teach the social constructs of race

“When I was in graduate school, I was tasked with developing a math lab in an elite elementary school. The first day I walked into the faculty lounge, the conversation was, ‘you’re the first colored person we’ve had in the lounge.’ And I thought, what color is that? And how do you start that conversation?” recounted Foster.

Race-related topics are multi-layered and complex, posing a challenge for educators who want to broach the subject matter. “The Crucial Conversation: Educating through an Anti-Racist Lens” provides a framework for faculty members to combat antiquated pedagogy and facilitate discussion that holistically introduces the topics to students.

As a senior professor of mathematics with nearly five decades of experience and as director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at PVAMU, Dr. Foster played a pivotal role as co-editor. Her contribution encompassed her years of instructional knowledge and personal accounts of racism and discrimination.

“When I was at the University of Houston, there were 11 Black students in my program. They had never seen that many Black faces. In my first math class, the professor said, ‘I don’t want any coloreds in my class,’” Dr. Foster recounts. “I could have been angry, but that statement came from a lack of education and ignorance. We have to have those conversations, and that’s what the book is about.”

The book is not the first to address race-related topics in the classroom, but it takes a modern approach in light of the events surrounding the murder of George Floyd.

“We’ve seen racism, but never placed in our faces like George Floyd. It was recorded and watched over and over again. We heard about what happened in the past, but to see somebody die right in front of your face is different for this generation. George Floyd and the incident with Sandra Bland in Prairie View hit the public in the face. Not just the United States, the entire world saw what happened and what’s still going on.”

The book is an opportunity to educate and engage students in dialogue that fosters critical thinking, provides context to understand existing inequitable systems and policies and allows students to form opinions. “Each chapter offers practical tools for generating productive dialogue,” said co-editor William T. Hoston, a professor of political science and director of the Mellon Center for Faculty Excellence at PVAMU. It’s a professional development resource to help educators advance an equitable school curriculum and classroom to represent all students while identifying and remedying the impact of individual biases.

The edited volume is a comprehensive collection of submissions from PVAMU faculty and staff members Beverly A. Sande, Stacie C. DeFreitas, Tiara Cross, Jamila Cherise Clayton, Nathan K. Mitchell, Quincy C. Moore, Marco T. Robinson, Camille S. Burnett and Stephanie Tilley. In addition to the contributions from the PVAMU faculty and staff members, the book also includes input from others across the higher education landscape.

With various backgrounds and disciplines and a diverse group of thought leaders, the content explores historical events, proven practices and practical techniques.

In addition to Foster and Hoston, the book is also co-edited by Farrah G. Cambrice, an associate professor of sociology at PVAMU.

“Our institutions are more diverse. We should all be facilitating and engaging in crucial conversations on our campuses. HBCUs are not exempt. We have to actively address equity, inclusion and justice on campuses and in our classroom communities,” explained Cambrice.

Ensuring Black and Brown Students are visible and valued

The need to dismantle oppressive academic systems and pursue change is apparent. But some lawmakers claim that exploring race in the classroom is divisive.

Texas State Senator Bryan Hughes says he doesn’t want any student to feel guilty about the actions of their ancestors. Foster questions why empathy and giving students of all races the dialogue to discuss issues across the racial divide is controversial.

“We can’t sugarcoat everything. Someone’s feelings may get hurt, but you have a population with hurt feelings for 400 years. I grew up in the civil rights movement. I’ve stood in the picket lines. I had people spit on me. Those are the facts. There is a way to teach the truth,” she said.

It’s also a fact that the country’s racial makeup is constantly evolving. Today, students of color comprise the majority of school-age children. In 2010, the White non-Hispanic population in the United States was 63.7%; in 2020, it decreased to 57.8%. Almost 12.5% of the population is Black, 17.4% is Hispanic, and close to 5.5% is Asian. The diffusion score, which measures the population diversity based on the combined percentage of the remaining racial and ethnic groups, accounts for 11.4% of the population.

The Hispanic population is the second largest racial or ethnic group in most counties in the United States. African Americans were the second-most prevalent racial group in southern, northeast and midwest counties. The 2020 Census results also showed that Hawaii had the highest diffusion score (21.8%), followed by Alaska (17.9%), Oklahoma (17.8%) and Nevada (16%).

Despite the increasing racial diversity throughout the country, Republican lawmakers in Tennessee and Oklahoma continue to advocate against CRT, banning instruction in public schools and universities. Similar bills are proposed in Louisiana and Texas to prohibit race-related teaching.

Critics fear that students, mainly white, will be confronted with ideas that are demonizing and damaging to their self-image. But the intent is to challenge the source of inequalities and the root of these systems in society and politics to transform the world for future generations. “We’re not attacking anybody. We’re creating a non-threatening space to have conversations,” said Foster. “If we don’t have these conversations, we will continue to have people mistreated.”

Students of underrepresented backgrounds want to feel respected and welcomed. They have questions, and it’s the educator’s role to provide answers. Otherwise, we’re doing students a disservice. All young people have a right to inclusive instruction and space to express their history and experienced racial tensions. We can’t change what happened yesterday, but we can redirect the attitudes of tomorrow.

Effectively teaching across disciplines: More than a conversation on race

Employing the book as a vehicle, instructors can deliver a comprehensive conversation that’s racially responsive, “developmentally appropriate and academically engaging for all students.” But content is only one aspect of preparing educators to lead critical race topics. It’s about pedagogy– how educators facilitate and present themes to students.

Educators are often well-versed in their field, but most have never learned how to teach. Foster wants professors to become aware of how they instruct race and racism, from their word choice to class design. “How do you stand with your class? Is it in the front, or are you engaging the room to ensure all students flourish and feel included?”

Awareness of inherent classroom bias and proper training can increase student success in all disciplines. “One of our primary goals was to spark dialogue among educators in different academic disciplines on approaching the topic of race in new ways,” said Hoston.

With the emergence of different fields in the last ten years, it’s the educator’s role to be aware of shifting student needs. “Our students come with a versatile set of skills. I want faculty to pull out the creative parts of their students to utilize those skills,” said Foster. No matter a student’s major or focus of study, they need the tools to thrive across the board.

As the director of the Center of Teaching Excellence, among other activities, Foster oversees faculty orientation and leadership training and provides coaching for teachers across the U.S. on alternate delivery styles. “We train teachers at Prairie View, and we want them to be able to go out and have the right kind of conversation,” said Foster.

“I help faculty members provide students with the best education possible so they can progress in a world different from the one we experienced. Unless you’re under 25, your students learn very differently from how you learned. I want professors to expose students to what will make them competitive in a global market.”

She works with faculty to examine their curriculum, identify irrelevant information, and determine what needs to be added or changed to nurture a holistic education.

One of PVAMU’s earlier presidents, Dr. Alvin I. Thomas, is Foster’s inspiration. He was a leader who wasn’t afraid to thrust faculty members into new challenges. “He said you’ll do it here because I want you prepared when you go out and have to do it somewhere else,” she recalls.

Starting the critical conversation to change the future

There’s no need to be fearful of history. It’s not a weapon or opinionated narration. History is a chance to objectively learn from the past, correct missteps and present-day discrimination and build a unified human race.

While some lawmakers seek to maintain an American history that erases the lived experiences of Black and Brown people, educators must provide a classroom experience “that affirms and validates the diversity of cultural and individual differences, fosters resilience and facilitates well-being and positive academic and mental health outcomes.”

“It is our responsibility to do what it takes to ensure everyone feels safe. There are too many things that create unsafe spaces now. Hopefully, this book will help present those safe spaces or allow the faculty to create those back-and-forth conversations. It’s not just about the faculty member giving their opinion, but having an open dialogue with students,” said Foster.

As the Supreme Court upheld in Brown v. Board of Education, “[e]ducation is the very foundation of good citizenship. [I]t is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values.” The Crucial Conversation: Educating through an Anti-Racist Lens will help educators do just that.