An Inspiring Biography of Merze Tate From Penn Professor Barbara Savage

Style Magazine Newswire | 10/3/2023, 1:21 p.m.

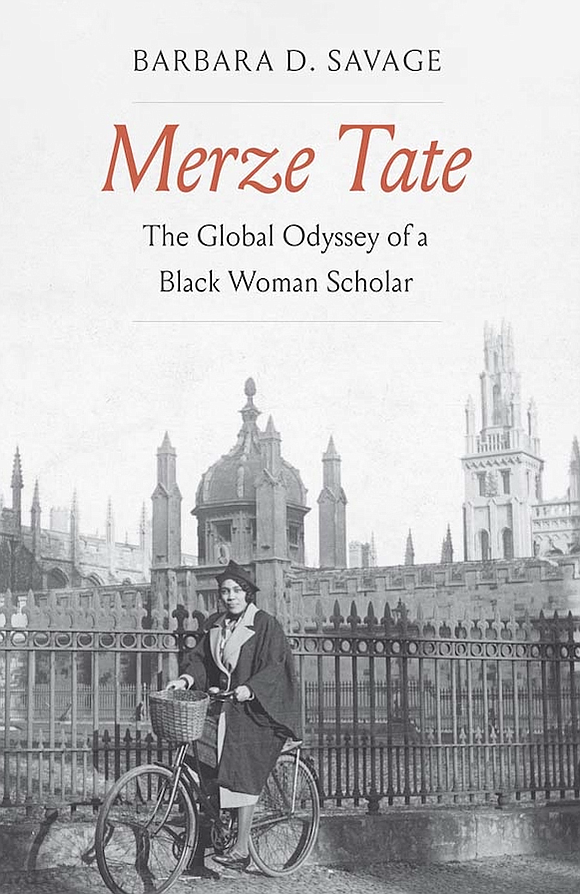

Born in rural Michigan at the turn of the century, Merze Tate was the first African-American woman to attend Oxford. She also graduated with a doctorate from Harvard, became a leading scholar on diplomatic history, colonialism, and nuclear arms, taught for 30-plus years at Howard, and kept seeking ever more knowledge throughout her life—reading, writing, and traveling the world with her camera. University of Pennsylvania professor Barbara Savage’s new biography MERZE TATE: THE GLOBAL ODYSSEY OF A BLACK WOMAN SCHOLAR (Yale University Press; November 2023) tells the astonishing story of a woman, who, despite living in what she called a “sex and race discriminating world,” never allowed her intellectual ambitions to be thwarted.

MERZE TATE is not only an incisive and compelling biography of a scholar who thrived despite steep obstacles, it’s also an ode to the quest for knowledge—the limitations it helps overcome and the experiences it opens. At a time when women, and Black women in particular, weren’t expected or even allowed to seek out or participate in the larger world, Tate was an irrepressible force. From her youngest years, she always sought more, and in her travels that took her from a farm in the Midwest to Kalamazoo to London to the world beyond, she never ceased to shatter expectations.

Savage places Tate’s accomplishments in the context of the larger Black world she lived in: the civic organizations and sorority that funded her, the other Black scholars that provided both professional and personal support over the decades, and the local newspapers that celebrated her accomplishments and travels. Based on more than a decade of research, Savage’s skilled rendering of Tate’s story also revives and critiques her prolific and prescient body of scholarship, celebrates a historical community of support for the social and intellectual power of Black women, and paints an inspiring picture of how far some of us will go to learn everything within our grasp.

Tate's life and work challenge provincial approaches to African American and American history, women's history, the history of education, diplomatic history, and international thought.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barbara D. Savage is a historian and the Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work includes Your Spirits Walk Beside Us, winner of the 2012 Grawemeyer Prize in Religion. She lives in Philadelphia, PA.

Q&A WITH BARBARA D. SAVAGE

In the book you write, “The more I learned, the clearer it became that (Tate’s) extraordinary life story and prodigious body of work still had much to teach all of us.” So, why a biography of Merze Tate? What can her life teach us?

To be perfectly honest, I still call myself Tate’s “reluctant biographer” because I never planned on writing a biography of her or anyone else for that matter. Here’s the unlikely story of a black girl born in rural Michigan in 1905 who imagines herself becoming a writer and a professor and a scholar and a world traveler. She was born into what she herself called a “sex and race discriminating world,” one where it was nearly impossible for women and black people to do what she wanted to do.

And yet, through her brilliance and hard work, she earned graduate degrees from Columbia in 1930, Oxford in 1935, and a doctorate from Harvard in 1941. She then joined the prestigious faculty of Howard University where she taught diplomatic history, and wrote five books during a very long life that ended in 1996. And yes she also had many unusual adventures, circling the globe twice, traveling solo.

Over the last decade, I have talked about her to a really wide variety of people here in the US and abroad. When people learn about her, they are as inspired as I am by her successes despite her disappointments, by her strengths as well as her weaknesses.

She always credited her success to other women, both Black and white, who helped her realize her ambitious dreams. As a black woman scholar myself, I have come to believe that Tate found me rather than the other way around. And that her perseverance and her boldness paved the way for the opportunities that have come to those of us born in these later times.

Tate is known in academic circles and has been widely honored posthumously, but she’s certainly not a household name. What can a biographer reveal through the non-famous that is harder to access in a work on a better-known subject?

Tate’s work recently has begun to receive some of the attention it has long deserved. That’s happening because her writing was so prescient and remains so relevant today on topics ranging from nuclear arms limitations to race and imperialism in India, Asia, the Pacific, and Africa.

We all have a tendency to return time and time again to “the usual subjects” or the people whose lives fit into the few categories or tropes that we use to discuss, in this case, black lives in the twentieth century, and black women’s lives in particular.

So by working on someone who did not fit many of those categories – she was not born in the south but on a farm in Michigan, she was not a man, but a professional woman who never married and had no children – I had to pay special attention to the particularities of her life story.

A “non-famous” but extraordinary life like hers raises questions about who gets judged to be worthy of remembering and who does not. Those questions are themselves mired in the very conditions that made her struggle to achieve so difficult. That in turn produces a history that privileges a very few at the expense of those who have been erased, rendered invisible, disregarded – even when their lives are every bit as compelling, as significant.

Tate said that her life would have been much different if she had been born in the Jim Crow South and not rural Michigan. What opportunities were she afforded by being born outside the South?

Had Tate been born in the South in 1905, she would not have had access to the elementary and secondary education she received in Michigan. Nor would she have been able to attend a state-funded teacher’s college along with white students in her home state.

But when she spoke of Mississippi, she also was referring to the sharecropping system throughout the South which denied black farmers access to land or home ownership and doomed black families to generations of laboring year in and year out with no prospects of escaping poverty or racism.

Her grandparents had migrated to Michigan on ox-drawn carts to claim land that would become theirs under the Homestead Act of 1862, which deeded land to those willing to come, clear it, and farm it. They were not sharecroppers, they were homesteaders able to support themselves by farming their own land and cutting timber.

Michigan was by no means a racial utopia, and she knew that. But she also meant that by not growing up in the segregated South, she had been spared the worst of the daily humiliations and hostilities and violence and abuse from white people intent on keeping segregation and white supremacy the law of the land.

After living in Michigan, Indianapolis, and London as a young woman, Tate took a job in segregated North Carolina. How did living in the South change her?

Tate moved to take a job at black colleges in North Carolina in 1935, after three years at Oxford. She literally got off the boat in NYC and took a train south, traveling on a Jim Crow car for the first time. There she was welcomed into a national community of black college teachers, which at that point meant you were going to be in the south, working at a crucial set of historically black colleges. So that was her home space so to speak, and she would say of her time there that it was a narrow world but a deep one. Still, she was living in a dangerous, legally segregated state, and she had to conform to that – buses, bus stations, restaurants. She left there in 1942 to head to that other southern space, Washington DC. We sometimes want to forget that it ALSO was a segregated, Jim Crow city – in my mind, living in NC simply helped her prepare for living in Washington DC.

Throughout Tate’s life, the quest for knowledge and education were guiding principles. As a scholar and longtime professor at Penn, clearly, that resonates with you. What insights did your personal story give you into Tate’s life?

I was born over a half-century after Tate but in still-segregated rural Virginia. At home, in school, and at church, nothing was reinforced more than the value of getting an education as the key to improving the lives of young black people. That’s part of the reason that I identified so easily with her quest for education. She did that at a time when everything conspired against women and black people being able to have access to even the most basic education, let alone college and graduate study.

I am proud to have spent the last 25 years working as Tate did, as a professor, a scholar, a teacher, a mentor. But this is not my first career; like many of my generation, I went directly from college to law school and then worked in Washington for over a decade.

In what I think of as an “early mid-life crisis,” I decided that I wanted to write and teach African-American history. That required me to find the courage to leave a city I loved, to take the financial risk of earning a doctorate in history in my mid-30s, and to start a new career.

So all of that helped me understand Tate’s drive to get an education, to aspire to be a scholar, a teacher, a writer – and to do it despite the barriers and sacrifices. Her struggles were far more difficult than mine of course, and with few rewards and privileges. But I still understood instinctively the power of her drive.

When Tate initially struggled academically at Oxford, she implored the administration to not hold her difficulties against future Black applicants. How was Tate affected by being, at times, the only black student or the first black woman to achieve what she did?

Tate’s plea represents an apt example of what I call in the book the “burden of racial representation,” here also expanded specifically into the burden of representation for black women, here in an intellectual setting. Of course, she did succeed and get that Oxford degree and the vulnerability in her plea—completely out of character for her (being a very prideful black woman)—came at one of the lowest points in her life. The idea that she would fail felt to her like both a personal and professional failure, but most deeply a failure for the race of people she represented – especially at a time when claims of black intellectual inferiority were so rampant (as they remain today). She literally embodied the counter-argument to that so that her success would be celebrated by black people for that very reason; her struggle was “our” struggle speaking as a black woman myself. And she could not bear the idea of failing her black women sorority members (Alpha Kappa Alpha) who gave her the graduate fellowship that sent her to Oxford. That burden of representation is ever-present, even today – and I feel it even in our conversation today. It’s always there, and certainly, my students feel it, too.

You write that Tate had “an obsessive need to travel and explore.” Do you think that was a desire to learn and see as much as possible or was there more to it?

Her ambition to travel the world started when she was a child when she became fascinated by a series of geography books with beautiful illustrations about children traveling the world. And so hers is a childhood obsession and she traveled solo around the world twice. So, she’s not just going to Paris and London, though she does do that of course, but she is in Cambodia, Thailand, Africa, the southwest Pacific, the Soviet Union, and spent a year traveling the vastness of India.

Her little blue passport entitled her to the privileges of her American citizenship at the time when that freedom was denied her at home. But she also needed to see things for herself, through in her own eyes – she was a keen photographer. And because she was a diplomatic historian, seeing the world was also intertwined with her research.

Even with all of that, the extent of her traveling and the priority she gave it – checking off a list of places she wanted to see – was also excessive. And exhausting to me as her biographer. When someone travels that much, we ask – what is she running away from? I concluded she was driven by what she was running toward – the wonderment of the lands and peoples of the world.