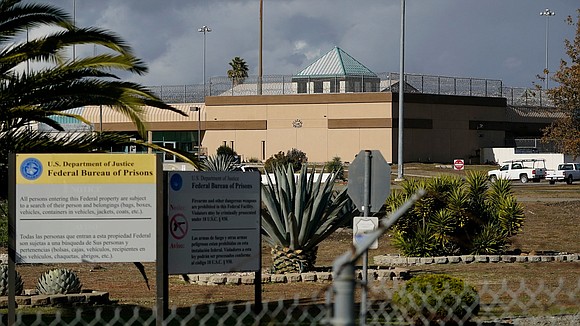

DOJ watchdog report finds chronic failures by Bureau of Prisons contributes to deaths of hundreds of inmates

Hannah Rabinowitz, CNN | 2/15/2024, 12:54 p.m.

Chronic failures by the Bureau of Prisons contributed to the deaths of hundreds of federal prison inmates, the Department of Justice’s Inspector General said in a blistering report released Thursday.

The report found that recurring failures within the Bureau of Prisons, such as inaccurate mental health screenings or prison staff missing inmate rounds, led to inmates dying in federal custody. Longstanding institutional issues also limited BOP’s ability to investigate inmate deaths and prevent similar conditions in the future, it said.

For years, the embattled Bureau of Prisons has been the subject of accusations by politicians, prisoner advocacy groups for mistreating or neglecting inmates.

The Justice Department itself has issued scathing rebukes against BOP, outlining serious mistakes that have led to the deaths of high-profile inmates like notorious Boston gangster and convicted murderer James “Whitey” Bulger, who was killed shortly after being transferred to a new prison, and financier Jeffrey Epstein, who died by suicide in his jail cell.

But the circumstances that led to Bulger and Epstein’s deaths are emblematic of wide-ranging and recurring issues within the federal prison system that affect hundreds of inmates across the country, the DOJ’s Office of Inspector General found in its report that outlined a system in crisis failing to protect its charges.

The 100-page report analyzed the circumstances of 344 inmates who died by suicide, homicide, accidents or other unknown factors between 2014 and 2021.

The OIG recommended several changes to BOP procedure, including developing strategies to ensure that inmate mental health is properly evaluated, that prison staff is taught to use defibrillators and naloxone, and to develop procedures that require inmate death records to be consistently completed and collected.

In response to the report, a BOP spokesperson said in a statement to CNN that BOP “acknowledges and concurs with the need for improvements” and is “dedicated to implementing these changes to ensure the safety and well-being of those in our custody.”

Issues with existing BOP standards

In several of the homicide and suicide cases examined by the OIG, inmates died after prison staff failed to meet standards outlined within BOPs own policies.

The report pointed to correctional officers who didn’t complete their assigned duties, improperly filled out paperwork, didn’t bring life-saving equipment when responding to an emergency, gave inaccurate or unclear information on the radio to medical staff, or didn’t know how to administer overdose medication naloxone.

For example, correctional staff failed to conduct the required rounds or inmate counts in restrictive housing units before the deaths of at least 86 inmates. In another 17 cases, staff failed to search or did not sufficiently search inmates cells, allowing them to poses excess medication, bed sheets or razors.

Investigators pointed to Epstein, noting that before his death he was able to amass an “excessive amount of linens.” In another case, prison staff claimed to have searched an inmate’s cell three times without finding contraband. Days later, the inmate died by a drug overdose after amassing more than 1,00 pills in their cell, the report says.

Some staff also allowed inmates to evade metal detectors, the report said, including in 11 homicide cases where inmates weren’t searched, were allowed to walk around metal detectors or not confronted after setting off metal detectors.

The OIG also said that guidelines to help prison staff investigate deaths once they had occurred often were adhered to. BOP was “unable to produce documentation required by its own policy for 43% of the inmate deaths in our scope,” the report says, including 117 cases where the BOP failed to acquire death certificates.

Prison suicide

Recurring violations of BOP’s own policies and operational failures inside prisons led to a staggering amount of inmate suicides, the OIG found, accounting for more than half of the deaths analyzed in their report.

Prison staff frequently did not properly evaluate inmates’ mental health, often categorizing inmates who later died by suicide with little to no mental health risks. Other inmates with documented mental health risks were isolated in a special housing unit (SHU) or did not receive the counseling they were supposed to and later died by suicide.

In one example highlighted in the report, prison health services staff did not refer an inmate who had swallowed razor blades for psychological help. The inmate went on to be repeatedly placed in the SHU for engaging in violence without the knowledge of the mental health staff at the facility, where he later died by hanging.

Staffing crisis

A staggering lack of health care and correctional staff within the prisons has also led to a diminished quality of inmate care, the OIG found.

In one particularly egregious example, the OIG described the lack of access to healthcare in the notorious Federal Correctional Institution Thomson in Illinois. When the OIG visited Thomson in 2022, according to the report, it had not had an on-side full-time physician for over a year. Additionally, nearly half of its nursing positions were vacant, the report said.

These vacancies can drastically affect quality of health care, the report said, or overwhelm staff so dramatically that they quit.

Staffing shortages have also forced some institutions to mandate available staff to work overtime shifts, in some cases working 16-hour days several times a week. Other staff members are asked to augment their responsibilities, at times forcing non-correctional officer staff to perform correctional duties – including one case where psychologists were assigned to correctional posts for more than two months.