Drake vs. the Beatles? Time to retire rap vs. rock cliché

CNN/Stylemagazine.com Newswire | 7/16/2018, 1:17 p.m.

By Jennifer Lynn Stoever

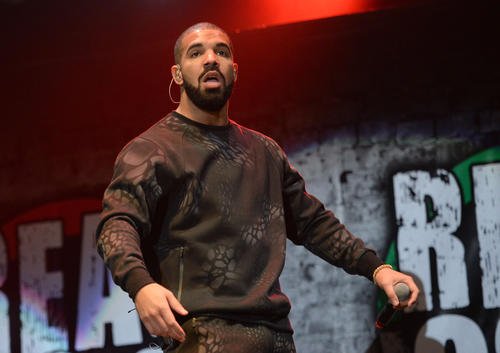

(CNN) -- Rapper Drake became the first artist to chart seven simultaneous Billboard Top 10 singles last week, besting the Beatles' record of five in 1964. In today's fractured media landscape, Drake's ability to get so many people bopping to "Nice For What," "Nonstop," "God's Plan," "In My Feelings," "I'm Upset," "Emotionless" and "Don't Matter To Me" deserves a tip of the hat, whether you rep Team Drizzy or not.

However, media "props" for Drake's feat have been restrained, with most coverage ultimately focused on the Fab Four. USA Today called the Beatles' record "historic," while The Wrap characterized Drake's accomplishment as invasion: "Drake has not only entered Beatles territory -- he's eclipsed it." Rolling Stone delegitimized Drake's success as "a display of commercial dominance so emphatic, it's almost cruel."

But, c'est la vie, right? Pop charts change, formats shift, even seemingly untouchable records fall. But why are the Beatles so sacred that their Top 5 record remains "historic" (though broken), while Drake's accomplishment represents "cruel" dominance? Where's this Drake hateration really coming from?

Perhaps it stems from the fact that Drake has legions of "female fans," a designation that has frustratingly been used throughout US music history as a sexist dis to signal an artist's lack of seriousness -- boy bands, girl groups, and bubble gum music, anyone? - -or a homophobic insult leveled at a performer's masculinity.

When influential DJ Funkmaster Flex of New York's Hot 97 got involved in some beef with Drake in 2016, for example, Flex taunted Drake on air: "Seventy percent of your fans wear high heels. The other 30% are guys who wear sandals. I'm not concerned about you, bro." It's no coincidence that just a few days after the "6 God" hit that Top 7, Twitter erupted with photos and videos of women chasing Drake around a video shoot in London, screaming and crying like it was, well, A Hard Day's Night in 1964.

Beyond the gender issue, by pitting "Nice for What" against "Can't Buy Me Love," are we rehearsing that tired conversation: rap vs. rock, beats vs. guitars, is rock dead (again) and did hip-hop kill it?

Both are well-worn paths to what's really at stake: the way American culture cultivates racial and gender hierarchies through music. Media shade over Drake's record has little to do with quality and much to do with the intersection of gender and what I call the sonic color line.

The desire to describe certain sounds as "black" or "white" -- or to hear them as "opposing" one another -- is a product of culture. These listening habits establish racial difference: that "sonic color line." Even though this process has a very long cultural history, our ears are trained to hear this as just the way things "naturally" are.

Coming this year, during the United States' most openly racist period since 1964, Drake "smashing" the Beatles' record carries racial symbolism. After all, the Beatles set their record just four months shy of the 1964 signing of the Civil Rights Act, a radical milestone whose results -- and immense backlash -- are still unfolding.

And just like any baseball "best" set before desegregation carries an asterisk, so should the Beatles' Top 5 record. Baby Boomer music fans in particular consider the Beatles the epitome of a "great" band, but rarely consider who determined the qualifications for "greatness" or how the sonic color line shaped those qualities.

Drake's accomplishment demands that we consider the long-standing connections between "great" and "white" in the world of charts, canons and awards (Remember #grammyssowhite? Last year's Kendrick Lamar Pulitzer Prize "controversy"?).

The rock vs. rap battlefield is littered with irony, precisely because America's sonic color line defines boundaries that don't actually exist, placing strict racial labels on music genres resistant to them. Early hip-hop DJs such as Afrika Bambaataa were rock fans, regularly sampling it in sets; Billy Squier's "The Big Beat" was a special Bambaataa favorite, as was "Did You See Me?", a 1980 song by black new-wave rockers the Bus Boys that proclaims "I bet you never heard music like this by spades."

As rap gained nationwide recognition in the 1980s, some American cultural gatekeepers deemed it derivative racial "noise" -- much as the 1950s mainstream sensationalized rock. Others felt automatically entitled to its genius: "Rap is rock after all," former Def Jam publicist Bill Adler claimed in 1991.

But maybe the reverse is true. Rock music may be the truly derivative racial "noise." We must remember the Beatles -- perpetually No. 1 one on Rolling Stone's "Greatest Artists of All Time" -- started as a rhythm-and-blues cover band. The Beatles owe serious debts to the black artists and music scene of their hometown of Liverpool and to the black American performers whose music fueled the so-called "British Invasion," particularly black women. Reportedly, the Liverpudlians' favorite singer was Motown star Mary Wells; they toured with her in 1964.

In 1963 alone, the Beatles released covers of songs originated by black female groups the Marvelettes ("Please Mr. Postman"), the Shirelles ("Baby It's You"), the Donays ("Devil in His Heart") and the Cookies ("Chains"). "Twist and Shout," one of the famed Top 5, was first performed in 1961 by a black group, the Top Notes.

As Maureen Mahon argues in her groundbreaking 2004 study Right to Rock, such covers laid the groundwork for the genre to become sonically "white" to mainstream American ears.

Given the segregation of America's record stores, airwaves, and pop charts -- not to mention the continued Jim Crow culture in the South and the North's concurrent white flight to the suburbs -- generations of white kids since may have never heard the originals or known the Beatles versions were covers.

The Beatles' covers helped cultivate the fan base that launched them onto America's charts; this earned them the fortune that ultimately enabled their later critically-lauded musical experimentation. The New York Times' 1967 review of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band," for example, opens by mentioning the unprecedented $100,000 the band spent to live up to their newly-established reputation as "the progenitors of a Pop avant garde."

In contrast, the 1964 Times' Beatles coverage focused largely on deriding female fans' "hysterical squeals," with little to no mention of the band's "historic" Billboard record at all. "Not even their mothers would claim that they sing well," the Los Angeles Times proclaimed that same year, "but the hirsute thickets they affect make them rememberable, and they project a certain kittenish charm which drives the immature, shall we say, ape." Ahem.

Such media misogyny -- and the tired, race-baiting rap vs. rock beef -- obscure the real "historic" headline connecting Drake and the Beatles: the power of women as American tastemakers. Women put the Beatles in the top 10 in 1964, and Drake's "female-friendly fan-base" put him there in 2018. In fact, both artists have endured homophobic taunts about being "girlish" (Beatles) or "soft" (Drake) because women backed their musical careers. Dismissed as hysterical "screaming groupies" back then and denigrated as hyper-reactive hashtagging "stans" now, female fans remain ignored, denigrated, and downright disrespected by American media, as if they haven't been utterly critical to American popular music.

Drake's Top 7 signals not the death of rock, but hopefully the end of white male musical gatekeeping. We have overlooked the influence of women's -- particularly black women's -- listening habits for far too long. If some long overdue R-E-S-P-E-C-T comes from this Beatles-Drake business, then I'll break out the champagne, papi.