What Many Africans Are Hoping To See In Beyoncé’s BLACK IS KING

Style Magazine Newswire | 7/31/2020, 8:14 a.m.

In March 2018, a month after the film "Black Panther" was released, the fictional country Wakanda was the fourth most-mentioned African country on Twitter -- after Egypt, South Africa and Kenya -- according to a 2019 study by the University of Southern California. The fact that Africa's fourth most-talked about country doesn't exist confirms just how powerful pop culture is in shaping our understanding of the world around us.

So when Beyoncé Knowles-Carter -- one of the most influential living artists on the planet -- released a teaser trailer for her new visual album "Black is King" in late June, featuring (as she described in an Instagram post about the project) "Black history and African tradition," some Africans didn't like it.

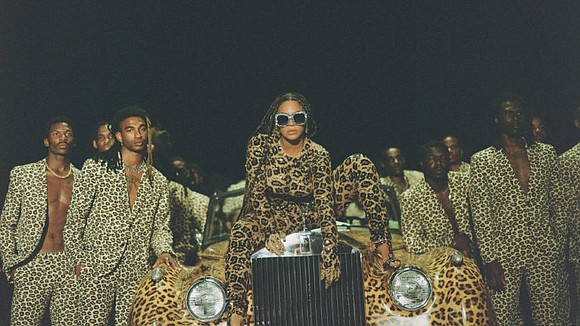

With its imagery of face and body paintings, feathers and animal fur, in celebrating our African traditions "Black is King," perhaps a little naively, missed the pulse of how many young, urban Africans -- both on the continent and the diaspora -- want to see themselves. They want to be presented in a more contemporary way, as global citizens representing a dynamic continent. Beyoncé picked the right story -- but may have given it the wrong framing.

In the film, she pays homage to what she called on Instagram "the breadth and beauty of black ancestry" and she is right that this is very much intertwined with the story, the history and the culture of this continent. And the trailer is certainly breathtaking, with exquisite cinematography, a haunting soundtrack, lavish visuals and beautifully laid-out sets - nothing less than we have come to expect from Queen Bey.

In mid-July, an additional trailer was released, but it did not quell the response to Beyonce's use of imagery or authority to try to tell Africa's story.

But why, some might reasonably ask, do chalk markings on black faces, naked male torsos and a preponderance of animal pelts provoke uncomfortable reactions from some Africans, when that is very much a part of our history and in some cases our existing cultures?

Answering that question has its innate challenges, especially if the short trailers simply omitted some context for the imagery that we'll get with the full album, but here I go...

The trap that Beyoncé's trailers fell into is the stereotypical (albeit visually compelling) story of a primitive continent that hasn't advanced much, which frustratingly still dominates too many Western perceptions. While the "Black is King" trailer captures the less harmful, more romantic aspects of the story, the other side of that same coin is the more harmful Afro-pessimistic view, which is prevalent in popular culture and media coverage. This view tends towards the "poverty is rife, violence is prevalent and disease is endemic" vision of Africa.

Although a global icon, Beyoncé's primary audience is in America, which according to a 2019 study on Africa in the US media conducted by the University of Southern California, is a country that knows, hears and sees very little about Africa. Perhaps this is why Beyoncé's efforts should be viewed as an opportunity to inform, educate and shape how this audience in particular sees the continent.

In the trailers, Beyonce appears to have done more than the US school system and media to advance discussion and awareness about Africa in the US and across the world. The mission behind the album is powerful, her influence is far reaching and her intentions are good.

She summed it up when she wrote on Instagram after the release of the first trailer: "I believe that when Black people tell our own stories, we can shift the axis of the world and tell our REAL history of generational wealth and richness of soul that are not told in our history books."

And she is so right about telling our own stories. But we still need to be careful which framing we give them.

We can tell ourselves it doesn't matter what "they" think. The truth is that it does matter -- because Western news and popular culture still largely dominate what Africans and the world consume and consequently shape what we all believe. Furthermore, studies have shown that narratives about Africa in Africa tend to mimic Western narratives about Africa, because often the sources for these stories come from outside the continent. The irony is that often Africans are learning about themselves and each other from western sources.

Beyonce's artistic interpretation of the continent showed us that even with the best intentions, we could inadvertently be feeding the narrative monster we should be trying to stifle.

Stories matter, but what matters even more is how we tell them and how we ensure we tell a multiplicity of stories about the continent. Stories that deliberately feed contextualized, nuanced narratives reflective of this modern, innovative, continent that knows its history and is proud of its culture.

So as we wait with great expectation for Beyoncé's celebration of black history and culture to drop fully on July 31, we have to hope the final product with her promise of "a modern twist and a universal message" will represent us as Africans in our plurality.