How Galveston Is Honoring Its Role As the Birthplace of Juneteenth

Style Magazine Newswire | 6/25/2021, 3:06 p.m.

As Galveston historian Samuel Collins III, whose own ancestors were freed as a result of the Juneteenth order, raised funds and installed a historical marker at the former Osterman Building—ravaged by Hurricane Carla and razed in the ’60s—but few people ever stopped to read it. Then, last year, amid the tragic deaths of Breonna Taylor and Houstonian George Floyd and massive protests over civil rights, Collins noticed a change. “All of the sudden, Juneteenth just exploded in popularity.

He also noticed the large, blank wall behind his historic marker and felt a lightbulb go on—why not memorialize the site in a more eye catching way? After securing permission from the building’s owners, Collins formed the Juneteenth Legacy Project and commissioned Adams, already familiar with his work.

In fact, among Adams’s 350 public art installations over a 25-year career in Houston (he’s originally from Wyoming), his vibrant Bayou City visual histories— murals, glass and tile mosaics, and sculpture—are known to amplify Black voices and shine a light on overlooked stories. He worked on Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses in the ’90s and on the 2000 Mickey Leland Memorial Park. In 2006, he rose to fame with mosaic mural Fruits of the Fifth Ward, which pays tribute to one of Houston’s oldest African American neighborhoods and the influential figures it produced—Barbara Jordan and Lightnin’ Hopkins among them. Elements of Change, highlighting the history of Emancipation Park, made its debut in 2020. Emancipation Park was founded by former slaves in 1872 as a safe space for future generations to celebrate Juneteenth. All of this work, says Adams, has led to Absolute Equality.

“I think this mural project will be a catalyst, and perhaps even a poster child for the holiday,” says Adams. “I’m really excited and honored to play a part in recognizing American history through the arts.”

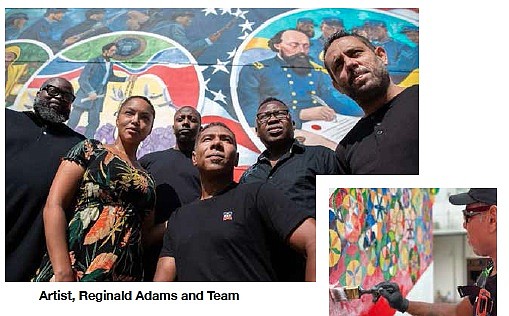

Rather than simply depicting the story of Juneteenth as people know it, Adams and his artistic team, the Creatives, mapped out a story that recontextualizes the holiday as a defining moment in the arc of Black American history, placing it within a larger historical context that begins with the transatlantic slave trade and continues with images of modern-day marchers, while weaving in Galveston’s own significant role.

“It is surreal at moments when we recognize we’re actually standing on the same ground where these events took place, just 150 years later,” he says. “It really was kind of an awakening. We are standing on the shoulders of our ancestors.”

“I’ve never done anything on this scale, at this level,” Adams says of the 5,000-square-foot piece. And though he originally wanted the community to help fill it in using a paint-by-number method, Covid put an end to that. Adams has incorporated drawings by students at the Nia Cultural Center, the project’s primary fiscal sponsor, along the right edge of the mural to represent the community.