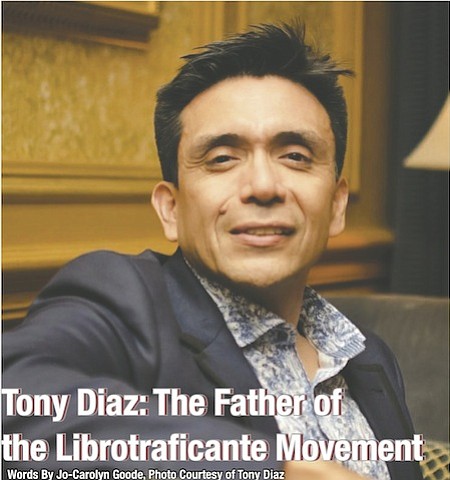

Tony Diaz: The Father of the Librotraficante Movement

Jo-Carolyn Goode | 9/22/2017, 7:08 a.m.

In celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, Houston Style Magazine is recognizing some of Houston’s most prominent Hispanics that are making a difference in their communities. We start with a man who is known not just in Houston but also throughout the state and the nation. Meet activist, author, radio host, and writer Tony Diaz.

Before he was campaigning to change the way Mexican American history is learned in schools and debating the banned of piñatas in Houston’s parks, he was a young boy growing up in Chicago, IL. Born to parents who were migrant workers, Diaz is the youngest of four brothers and four sisters. All of his family’s hopes and dreams were placed on him, as he was the only one in his family who went to school fulltime.

“Having one of the kids study all the time was a big moment for the family,” Diaz recalled. “There was one thing I remember about being a kid and that was the importance of education. “

He knew how important it was to his parents that he got the best education possible so they sacrifice everything to ensure that he got it. Diaz was the first in his family to graduate high school. He then left Chicago to come to Houston to attend the prestigious creative writing program at the University of Houston. He described his acceptance to UH as thrilling as it was a visible sign of his success that he was proud to show his parents and one of his three life’s goals. The others were to earn a black belt in Tae Kwon Do and published an award-winning book. He did those too.

Initially, when Diaz set foot in Houston he thought he would earn his master's degree and return to his beloved Chicago. But Houston took a hold of him and wouldn’t let go. He fell in love with the city. “I think what was eye-opening to me is that it seemed that it was a wider range of opportunities in Houston, especially for me at the time. And, also in my humble estimation, I think that for my access to education there were more opportunities for myself and Latinos in Houston.” Diaz continued, “I think I have been able to accomplish a lot differently than I would have accomplished in Chicago only because it is more open. There is more room for trying on projects.”

Community activism has become one of his biggest, most challenging and most rewarding project. With interest sparked when he was very young in Chicago, Diaz saw first hand the before and after effects of how speaking up for your rights changed people and communities. He learned how unions worked together, communities operated as a unit and the power of language. That initial spark would grow into a flame that is fueling him in his activism today.

He began his fight using his most powerful skill, language, by establishing Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say (NP). Originally NP was a monthly reading series featuring nationally published authors and writers from the community. Three years after its founding, the group would birth the Nuestra Palabra Radio Show on 90.1 FM. KPFT. The popularity of both NP and the radio show gave Diaz the idea to create an event that brought Edward James Olmos Latino Book and Family Festival that was attended by more than 15,000 people. All of these entities would tie together to form the Librotraficante Movement, which defies the far right attack on ethnic studies and freedom of speech. Librotraficante translates to mean book trafficker.

Tucson public schools in Arizona didn’t know what they had unleashed when they dismantled the ethnic studies programs from high schools taking away numerous books by notable Latino writers. Books were removed as a resulted of legislation passed by Arizona Governor Jan Brewer. Arizona House Bill 2281 prohibited courses that promoted the overthrow of the U.S. government, promoted resentment toward a race or a class of people, were designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group or advocated ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals. Schools caught violating the law that went into effect in May 2010 could lose state funding. Not under the watch of NP, they wouldn’t stand for it. Diaz along with NP members began an underground library of sorts smuggling the banned books back to Arizona. The group would establish four such libraries with over a 1,000 books. This would be the start of the Librotraficante Movement.

The movement would take roots in Texas when similar legislation in the form of Texas House Bill 1938 and Senate Bill 1128 was brought to the table to eliminate ethnic and women studies courses from Texas colleges. His group again used the power of language to fight the system.

Now Diaz has gone back to his roots as a writer with his book The Mexican American Studies Toolkit to lead students to discover what it means to be Mexican American. It is his hope that once kids learn of the history of Mexican Americans they then will be intrigued to learn about other cultures. “This is not a course for Mexican Americans but for all Texans. I hope it starts a resurgence in all the different histories that have led up to us. So to me, that is the main message of the toolkit that we have this rich shared history that can be engaging and powerful to uncover but we can do it together,” said Diaz.

It is an idea and concept that he calls Quantum Demographics. “If I am fulfilled with my history and culture I have the wisdom and the actual framework to find bridges to other cultures that may not seem to have elements in common but do. And I can image where years down the line through incredible courses we are talking about that in class. We can investigate where Asian and Mexican Americans combine, Chinese and Mexican Americans combine, and African and Mexican Americans have worked together. But right now we are at the starting point because it is still very new and controversial.”

Controversy has never stopped him before and it won’t stop him now. He is in it for the long haul. The movement has already seen success, as the Arizona legislation was deemed to show discriminatory intent by a federal judge and a portion of the bill was struck down. In Texas, the fight continues as Diaz marches on to change what students learn with his book, The Mexican American Toolkit. It is one of two ethnic-based books being looked at for adoption by the Texas Board of Education.

The Librotraficante Movement is becoming even more needed with the new immigration legislation of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals up for debate. Many youth are not just scared but downright terrified for themselves and their families. Many have come to Diaz questioning why they should stay in school if it is just going to be taken away. Diaz, of course, tells them to stay in school as he continues to fight for their rights.

“Every culture has something to contribute,” said Diaz, as he spoke about how he grew up where Mexican contributions were not praised. His family was sometimes frowned upon for their accent and attire. “I also knew that the same culture inspired me to work, respect my family and gave me a family that totally believed in me,” Diaz said these things are a wonderful component of being Mexican American and what makes him have so much pride in his heritage and the reason he continues to fight for the Mexican American story to be taught in schools. “That’s why education is powerful because in one generation my family has gone from the farm fields where now I can represent my culture on the national stage.”

Diaz’s fight is one that will not just benefit Mexican Americans but all minorities. Everyone deserves the right to have their story told in a nonbiased, detailed, truth. It is the only way that we can respect each other as people first and our different cultures second. Education and understanding of others is the universal way to humanize the world and make everyone’s life the better for it.

For more information, visit themastoolkit.org